I’m a musician. A vocal performance major. I practice everyday. It’s the first thing on my mind when I wake up and the last thing before bed. Music surrounds me constantly, filling my mind like a perpetual soundtrack. Mostly, this is great because it’s what I love most. I spend every day studying, listening to, analyzing, eating, breathing, and sleeping music.

But, in spite of all this, I don’t sing nearly as much as I used to. I used to sing all the time. Alone, with friends, in my room, outside, for an audience, by myself, every song I knew, as many times as I wanted. It was a way for me to communicate, more natural and expressive than speech.

But now every time I sing it’s about technique. Singing isn’t free anymore, it’s either correct, or it’s just wrong and potentially “hazardous to my vocal health.”

On some levels that’s ok. The better my technique becomes, the more easily I can express the music. The freer the vocal production, the better chance that I will have a long and healthy career. But sometimes I worry that I’m thinking too much about technique when I sing. Particularly because nowadays, those precious hours in the practice room are pretty much the only times I sing. As the years go by, I find myself spontaneously bursting into song less frequently. (Sadly, I hardly ever sing in the shower anymore.) Maybe I’m just “growing up,” but I think it’s something more. Every time I vocalize, I worry about placement and breath and tone. I can’t just open my mouth and let whatever I’m feeling come out. It has to be “right.”

And therefore, when it counts, I don’t worry enough about what I’m singing. My time in the practice room is spent primarily working on the technicalities of being musical. I show up to lessons and coachings struggling to explain what I’m singing about because, though I can translate all the words, I haven’t thought about WHY I’m singing them. I have fallen into a trap common among young, highly –trained conservatory singers: I’ve become a (somewhat) technically-proficient robot.

This is majorly unfortunate. Singing is human. It gives voice to everything we can’t put into words. That’s why it drives me nuts when people claim they “don’t want to sing around me” because (as a music major) “I might judge them.” No. For heaven’s sake—SING! If something is stirring you to sing then by all means: do it!! We can’t go around judging people constantly because that would be exhausting, and it would make us incredibly cynical. The ultimate purpose of music can’t be technical perfection because that wouldn’t move us. Even in the Western classical musical tradition, where seemingly everything explicitly stated, music cannot be solely about placement, articulation, rhythm etc. There is something more. Something all great musicians bring to their music, making it unique while technically brilliant, and still allowing the composers’ intentions to shine through. That is passion, or soul, or heart. Without this, a “perfect” piece of music will feel cold, and audiences, judges, and audition panels can tell.

In this blog, I’d like to continue researching and analyzing music, but with a new focus on my current repertoire, in addition to the study of timbre in music. I love learning about music, but I need to organize the information I study into knowledge that I can apply. I want to have something meaningful to put into every song. And so I’d like to use this space to share discoveries I’ve made about the music I’m working on. I’m hoping it will encourage me to put meaning back into everything I sing. And perhaps eventually, I’ll find my voice.

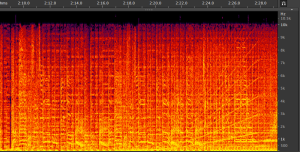

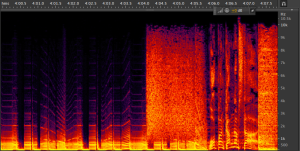

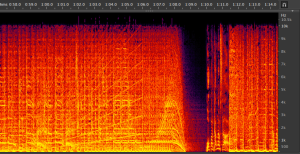

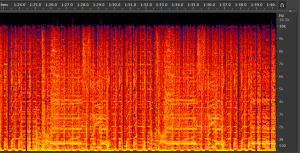

There are so many amazing things to discuss about music, but so often conversation centers around the audial rather than the visual. The visual aspect of music creation is critical to consider, because we humans are such visual creatures. Connecting what we hear to what we see is an unconscious but vital act, and it undeniably adds interest. Consider Fantasia—famous works of music set to cartoons. Children (and adults!) are given something concrete to watch, and the musical stories become much easier to appreciate. Attempting to make a 5 year-old sit still for even half an hour while listening to a symphony on CD would be very difficult. But pop Fantasia in the DVD player? Now you have a captive audience.

There are so many amazing things to discuss about music, but so often conversation centers around the audial rather than the visual. The visual aspect of music creation is critical to consider, because we humans are such visual creatures. Connecting what we hear to what we see is an unconscious but vital act, and it undeniably adds interest. Consider Fantasia—famous works of music set to cartoons. Children (and adults!) are given something concrete to watch, and the musical stories become much easier to appreciate. Attempting to make a 5 year-old sit still for even half an hour while listening to a symphony on CD would be very difficult. But pop Fantasia in the DVD player? Now you have a captive audience.